Like any post-Soviet country, Bulgaria has a wealth of socialist-realist art left over. Socialist realism is a style of art that’s one of the things most indelibly associated with Communism. Marxism-Leninism would create a proletarian paradise, a world of plenty in which individuals didn’t suffer the alienation that capitalist exploitation. In a world like this, what would be the point of representing something that didn’t exist?

Like any post-Soviet country, Bulgaria has a wealth of socialist-realist art left over. Socialist realism is a style of art that’s one of the things most indelibly associated with Communism. Marxism-Leninism would create a proletarian paradise, a world of plenty in which individuals didn’t suffer the alienation that capitalist exploitation. In a world like this, what would be the point of representing something that didn’t exist?

Socialist realism, reacting against the avant-garde trends of styles like Expressionism, sought to glorify this world that workers had created. The fact that the style avoided abstract forms was also an ideological rejection of the “decadent” values of other art. This was art that would speak to all of society, not solely the bourgeois leisure classes, whose domination of the means of production afforded them the time to ruminate about what that cluster of cubes and cones represents. Art that invites one sole interpretation (Like “Youth Meeting at Kilifarevo Village to Send Worker-Peasant Delegation to the USSR”) is also a useful tool to impose uniformity of thought, at least on paper.

Factory worker snaps cameraphone picture

Since socialist realism was the official state style of the Eastern block, art was the site of a heated Cold War battle. During the Red Scare, American reactionaries decried, hunted, and blacklisted countless artists who possessed even the most tenuous connections to socialism. Concurrently, the CIA was covertly funding modern art through countless government-backed funds and foundations. CIA money brought abstract expressionist artists like Jackson Pollock, Mark Rothko, and Willem de Koonig to the world through a fruitful relationship between the Museum of Modern Art (MoMA) and America’s clandestine services. Music journalist Adam Krause explains:

Why did abstract expressionism fit the CIA’s needs so well? The CIA’s goal in the Cultural Cold War was not just the denigration of Soviet Communism, but the promotion of the free market as well. Jackson Pollock and the other abstract expressionists were useful for each of these goals. The collectivism glorified by (the often rigid and never abstract) Soviet Socialist Realism could be set in stark opposition to the rugged individualism and “freedom” of these distinctly American abstract expressionists.

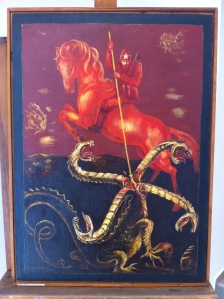

A Communist St. George (Bulgaria’s patron saint) vanquishes the many-headed chimera of fascist imperialism

Just as indelibly as rock and roll is associated with America (and later, Britain), the visual signs of socialist realism will be instantly recognizable to those who visit the Museum of Socialist Art. As mandated by the Bulgarian Communist Party, art featured workers manning gargantuan machines in factories and farmers reaping wheat in the fields. The museum’s exhibits are devoted to the September uprising of 1923 (“then defined as the first anti-fascist uprising”), the Second World War, “portraits of the great leaders,” and “various topics, some related to socialist construction – co-operating on the land, the brigadier movement, industrialization.” A legacy of “great leaders,” engineering achievments, and defeating Nazis. Say what you will about the shortcomings of Marxism-Leninism: things were built to last, and they really hated fascists. Continue reading →